I’m teaching a playwriting class right now, and we’re nearing the end of the term where students will submit their final drafts of a one-act play. Our discussions have sparked fascinating conversations about narrative structure and tension. During a recent one-on-one, a student brought in a twisty thriller that reminded me of two masters of the genre: Agatha Christie, about whom I know a little, and one of my all-time favourite television shows, Columbo.

During our session, we explored the radically different approaches these two masters take to the mystery format. Christie, with her “whodunits,” keeps readers guessing until the final pages when Poirot or Marple gathers everyone in the drawing room and theatrically reveals the culprit. This form makes sense when we are in just as much suspense as the characters.

Columbo, on the other hand, is not a traditional mystery. We’re shown the murder in the first ten minutes—the mystery, or puzzle, is how Lieutenant Columbo figures it out. Where Christie creates tension by delaying the reveal, Columbo builds it by inviting us into the cat-and-mouse game of psychological pressure, revealing character as the key to unraveling crime.

I used to watch Columbo with my mom. Our game was to determine when we thought Columbo suspected the killer (the earlier the better), and when we thought he had enough evidence to make the arrest (the later the better). We’d agree that Columbo’s whole personality was an act. The only time he seems to lose his cool (with Leonard Nimoy in “A Stitch in Crime”) is actually ruse to push the murderer to reveal himself. In fact, one fan theory of Columbo is that his library of working class anecdotes are all entirely made-up—a fictional world the detective uses to ensnare his suspects.

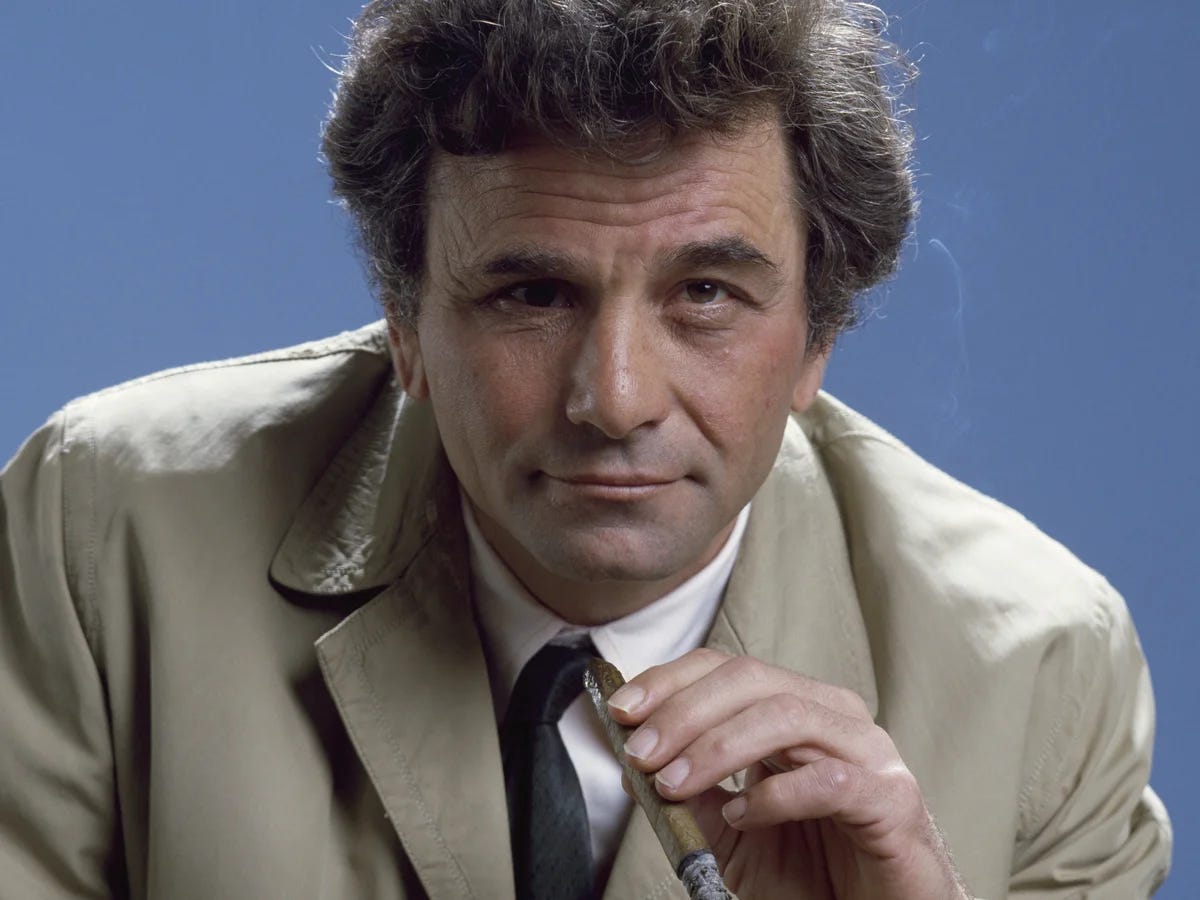

Over the years, I’ve seen every single episode. Stephen Fry once called it one of the greatest television series ever made, and I’m inclined to agree. There‘s something uniquely satisfying about watching Peter Falk’s rumpled detective with his perpetually unlit cigar, glass eye, and apparent bumbling gradually reveal his uncanny wit.

Revelation and Self-Incrimination

Episodes where Columbo simply presents evidence he’s already gathered feel somewhat deflated. Take “Columbo Goes to College,” where Columbo sets a trap for two cocky students who murdered their professor. The episode is entertaining, but the ending—where Columbo reveals he’s been recording their conversation—lacks the psychological tension that makes the best episodes so memorable. It’s too mechanical, too straightforward. The satisfaction doesn’t come from the revelation of evidence, but from the psychological journey to obtain it.

What makes Columbo’s traps so compelling isn’t just the evidence—it’s the emotional and psychological toll they take on the killer. The truly great Columbo episodes follow a pattern where the lieutenant applies pressure until the killer self-incriminates, creating situations where murderers must take actions that inadvertently reveal their guilt.

"Any Old Port in a Storm" perfectly demonstrates this technique. Donald Pleasence plays Adrian Carsini, a wine connoisseur who murders his brother to prevent him from selling the family winery. Columbo gradually chips away at Carsini’s composure, but the brilliant stroke comes when he mentions that a wine collection was stored at improper temperatures after the murder. The wine expert in Carsini can’t help but react with visible distress—he cares more about the spoiled wine than covering his tracks. This emotional response betrays his guilt in a way no physical evidence could.

In “Negative Reaction”, Dick Van Dyke plays Paul Galesko, a famous photographer who murders his wealthy, domineering wife and frames a recently released convict for the crime. Throughout the episode, Columbo recognizes the perfectionism that drives Galesko’s art. The detective’s masterstroke comes when he deliberately stages a false accusation using a mirror-inverted version of the kidnapping photo Galesko used to fabricate his alibi. When Columbo claims the original photo was accidentally destroyed, the increasingly agitated Galesko—determined to prove Columbo wrong—instinctively grabs the exact camera from a shelf containing a dozen others and pulls out the negative still inside it. There was no way he could have known which specific camera contained the negative unless he was the killer himself.”

Perhaps my favourite example is “Double Exposure,” where Robert Culp plays a motivation research specialist who uses subliminal imagery to commit murder. In a brilliant reversal, Columbo turns the killer’s own technique against him. During a screening, Columbo inserts subliminal cuts showing himself searching Keppel’s office. The increasingly paranoid Keppel can’t help but rush to check if the murder weapon is still safely concealed. Columbo and a photographer are waiting to catch him in the act, and discover the hidden gun. It’s the perfect example of Columbo understanding his quarry so thoroughly that he can anticipate and manipulate their behaviour, and how Columbo needed a piece of evidence that only the killer could give away.

All that said, Columbo’s methods might not hold up in court. A couple posts at The Columbophile Blog reveal that for a number of cases, include Double Exposure, the killer would walk free.

Hey! Enjoying this? Share it with someone you think would dig it too, and nudge them to subscribe. Like and comment—I’d love to hear what you think!

The Dance of Detective and Murderer: Empathy as Investigation

There’s something almost romantic about the way Columbo interacts with his suspects. It’s a delicate dance, with the lieutenant circling ever closer, retreating, then advancing again. These aren’t just cat-and-mouse games; they’re elaborate courtships of sorts, filled with mutual admiration and veiled threats concealed beneath polite conversation over brandy or fine food.

Take Jack Cassidy's elegant murderers in “Murder by the Book” (directed by a young Steven Spielberg) or “Now You See Him.” Columbo seems genuinely fascinated by these charming, cultured killers. He flatters them, asks for their advice, even seems to enjoy their company. The killers, in turn, often can’t help but like Columbo despite the threat he poses. There’s a magnetism to these encounters: a tension of attraction and repulsion that drives the narrative forward.

It might seem like the show romanticizes upper-class murder, with its parade of wealthy, sophisticated killers living in modernist mansions. But what Columbo actually gives us is a powerful demonstration of empathy as an investigative tool.

Unlike Sherlock Holmes, who solves crimes through cold, calculating reasoning and an encyclopedic knowledge of ash types, Columbo solves crimes by understanding people. He gets inside the killer’s head, appreciates their motivations, and often even sympathizes with them. When Adrian Carsini is finally caught in "Any Old Port in a Storm," Columbo admits he’s come to admire the murderer’s dedication to wine. Before taking Abigail Mitchell to jail in "Try and Catch Me," he tells her that he’d probably have done the same thing in her position.

This empathetic approach stands in stark contrast to the clinical detachment of other fictional detectives. Columbo doesn’t just want to know how the murder was committed; he wants to understand why. He inhabits the emotional world of the killer and uses that understanding to bring them to justice.

The final moments of many episodes showcase this complex relationship beautifully. There’s often a mutual respect, even fondness, between Columbo and his co-star at the moment of capture. There's a quiet acknowledgment, almost tender in its restraint, that the game is over. He offers Patrick McGoohan a light for his cigar in "Identity Crisis."

The power of Columbo’s dramatic structure lies in its immediacy. Unlike Christie’s retrospective reveals, these moments happen in real time—we watch the killer react, make a decision, and seal their own fate. When Miss Marple explains how she knew the butler did it, we’re looking backward at completed events. But when Columbo maneuvers a killer into revealing themselves, we’re watching justice unfold before our eyes, creating a uniquely tense viewing experience.

Lessons

The best Columbo episodes don’t just tell us that the killer has been caught—they show us the exact moment when the killer realizes it themselves. That moment of recognition, when all the lieutenant’s seemingly disconnected questions suddenly form a perfect, inescapable trap, is what makes Columbo one of classic television’s greatest achievements.

There’s a strange comfort in watching Lieutenant Columbo, with his wrinkled raincoat and beat-up Peugeot, bring down wealthy, powerful, arrogant killers who thought themselves above the law. Columbo teaches us something profound about both detection and storytelling: that understanding human nature—not just evidence or logic—is what can ultimately reveal truth.

In the end, perhaps that’s the most enduring lesson from this remarkable show: the most powerful mysteries aren’t solved through brilliant deduction alone, but through the messy, complicated, and deeply human art of empathy. It’s not just about catching the murderer—it’s about truly seeing them.

Did you enjoy this piece? Would you value future interviews like this? If so, would you prefer more or less detail? What kind of questions would you like to be asked? Let me know!

Reading and Listening

Halfway through On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder. Snyder is one of three leading scholars who are leaving Trump’s United States for a teaching gig at the University of Toronto.

Continuing The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, in a very similar vein to Snyder’s book.

Quote of the Week

“We wanted to keep him almost mythological. He comes from nowhere and goes back to nowhere.”

— William Link, one of the co-creators of Columbo